-

-

Sunrise at the Vortex is the second solo exhibition by Nima Nabavi at The Third Line. Featuring a selection of new works made by the artist between 2022 and 2025, the show marks a significant evolution in his practice, both conceptually and technically. Rooted in his travels to sites across the world considered to be energy centers by different communities, the works reflect Nabavi’s deepened commitment to introspection, geometry, and modes of making that embrace technology alongside traditional tools.

-

Nima Nabavi. Photo by Tonee Harbert.

Nima Nabavi. Photo by Tonee Harbert. -

-

I.W.: Roswell2223 (2023) was drawn meticulously over the course of a year. Could you describe the process of conceiving and executing this piece? You also worked on the piece while it was on view at the Roswell Museum in New Mexico, the United States, so that visitors could observe your process and speak with you. What did this experience teach you about your practice, yourself, and/or the world?

N.N.: My residency at Roswell marked the first time I had access to a standalone studio. Until then, I had always just worked on a kitchen table in my living room, which naturally limited the scale of my work. I arrived at Roswell without a specific plan, but when I saw the size of the space and the timespan of the program sunk in, I started thinking about making a single piece that would take up all of the space and time I had been gifted. I bought the largest roll of canvas I could find (18 feet by 6 feet), the biggest ruler I could find (9 feet long), and hundreds of markers in 17 colors. I then rolled out the canvas on the floor and started working on the piece line by line.

-

-

The pace of the project was so drawn out that daily progress was almost indiscernible, and it started to feel like life itself—how we grow into different versions of ourselves without realizing that transformation.

I had very little idea of the direction of the work. With a piece that big, you just need to take it one layer at a time and spend a lot of time contemplating every next step. The process was physically taxing—I was kneeling, squatting, sitting and bending over for hours on end, but being able to literally sit inside the work and be engulfed by it also brought so much joy. The pace of the project was so drawn out that daily progress was almost indiscernible, and it started to feel like life itself—how we grow into different versions of ourselves without realizing that transformation. There were some good days and some bad days, but the underlying intention to create a beautiful piece got it to where it was always supposed to be.

For about 6 weeks towards the end of the residency, I moved my studio into the Roswell Museum and continued working on the piece during regular museum hours, which allowed visitors to engage with me. Roswell is situated at the intersection of highways used by many travelers when driving across the state. It is near mystical national parks like the Carlsbad Caverns and White Sands, and it also has a bit of a tourist appeal stemming from the reported UFO crash in 1947. For these reasons, museum visitors were a wide spectrum of curious and open-minded people who were just passing through the town on their journeys, not expecting to end up at an art museum. They were often surprised to find someone actively making art in the space and were ready to spend lots of time speaking with me. It was fascinating to hear what each person saw in the piece—the unique ways in which they found meaning in the abstraction. I think my presence made the work accessible to the visitors, and their unfiltered reactions made their emotions accessible to me. These interactions were deeply rewarding, as I could see the effect my work could have on people outside of the art world or academia. This experience recalibrated the compass of my work towards drawing out these visceral and universal reactions. I want to make work that sparks a sense of joy and wonder in anyone who encounters it.

-

I.W.: It seems intuition plays an important role in the making of your pieces. Could you expand upon this aspect a little more?

N.N.: The type of work I make has infinite potential start and end points, so knowing where to begin and when I’m done is always a challenge. Usually, I commence at a point of curiosity that emerged while making a previous artwork. It’s hard to fully visualize what the work will look like at the outset. As I continue, I reach a point where something other than what I planned starts speaking to me. Once a piece is in motion, it gains its own momentum—it can veer into a clear direction, or it might require sitting with it, figuring out where it wants to go. If that pull is strong enough, I follow it. With Roswell2223 (2023) for instance, I kept a ladder beside the canvas and would climb up to gaze into the piece from above, often for an hour at a time. I tried to understand where it wanted to go next—what felt right and comfortable for the piece. As for knowing when a piece is finished, I rely on this feeling—like reaching the end of a story. That’s when I know its work is complete.

-

Nima Nabavi, Beautyland, 2024, Archival Ink on Paper, 13¾ x 13¾ in., 35 x 35 cm, 24½ x 24½ x 1⅛ in. (framed), 62.3 x 62.3 x 3 cm (framed)

Nima Nabavi, Beautyland, 2024, Archival Ink on Paper, 13¾ x 13¾ in., 35 x 35 cm, 24½ x 24½ x 1⅛ in. (framed), 62.3 x 62.3 x 3 cm (framed) -

And so I started experimenting with pen-plotters. When I first saw one, I instantly knew that I could incorporate it in my practice. It’s a very simple machine in its design; it holds a pen and draws one line at a time according your instructions. It felt like a studio assistant that actually spoke my visual language. To work with a pen-plotter, I draw the work on the computer first in the same way I would on paper, convert the drawings into layers of color, convert the layers into code, and then send that information to the pen-plotter to execute. The process turned out to be much more complex and time-consuming than just drawing the works myself, also because it introduced a huge chunk of error-prone unpredictability. However, it unlocked deeper dimensions in my work, not to mention that it freed me from the physical pain of manual drawing. With the pen-plotter, I can introduce curved lines, dots, and new angles in my works. I can layer my works in deeper saturations than ever before and experiment multiple color combinations.

I’ve also been revisiting digital animation recently. Digital work has always been a part of my practice; my first solo show at The Third Line, 1,2,3 (2018), included a digital animation. Last month, I was invited by Jameel Arts Centre to create a digital animation that would be projection-mapped onto a facade of their building. At Sunrise at the Vortex, I’m presenting The Pull of The Pulse (2025), my most complex animation to date, featuring 360 frames that I drew digitally. It has a meditative and transformative appeal, inviting people to spend time with it. These types of works ask people to interact with them in a totally different way than with a framed painting, and I love that I can use different mediums to connect with people.

-

I have all of these ideas inside me that I want to put out into the world, but my time on earth is finite. I’m committed to using whatever tools I can, whether they are traditional or technological, to bring these artworks to life. The most important part is that the work gets done and people get to see it. Methodology doesn’t define my practice—I will never make work in a way that is more difficult than it needs to be, and I will never undercut what the work requires either. I want to bring these things to life in their fullest and most honest manifestations.

-

Observe what you gravitate towards, as if you were in an open field, letting your curiosity pull you one way or the other.

I.W.: Your works invite viewers to lose themselves in complex patterns and layered forms. How would you like visitors to the exhibition at The Third Line to engage with your works?

N.N.: I want people to be at ease. Take your time—don’t feel forced or rushed. Observe what you gravitate towards, as if you were in an open field, letting your curiosity pull you one way or the other. Sometimes we overcomplicate how we look at art. The central piece, Roswell2223 (2023) has a lot to look at, so feel free to sit with it for a bit and see how deep it pulls you in. The Pull of The Pulse (2025) is quite meditative and behaves very differently from the drawings, so give it space too and maybe hang out for a while. I think the biggest compliment to me would be that viewers felt welcome, comfortable and at home in the exhibition.

-

-

Nima Nabavi, Series 9, Artwork 1 (Yellow, Red, Orange), 2025, Archival Ink on Paper, 9 x 9 in., 23 x 23 cm, 15 x 15 x 1⅛ in. (framed), 38 x 38, x 3 cm (framed)

-

Nima Nabavi, Series 9, Artwork 2 (Red, Orange, Pink), 2025, Archival Ink on Paper, 9 x 9 in., 23 x 23 cm, 15 x 15 x 1⅛ in. (framed), 38 x 38 x 3 cm (framed)

-

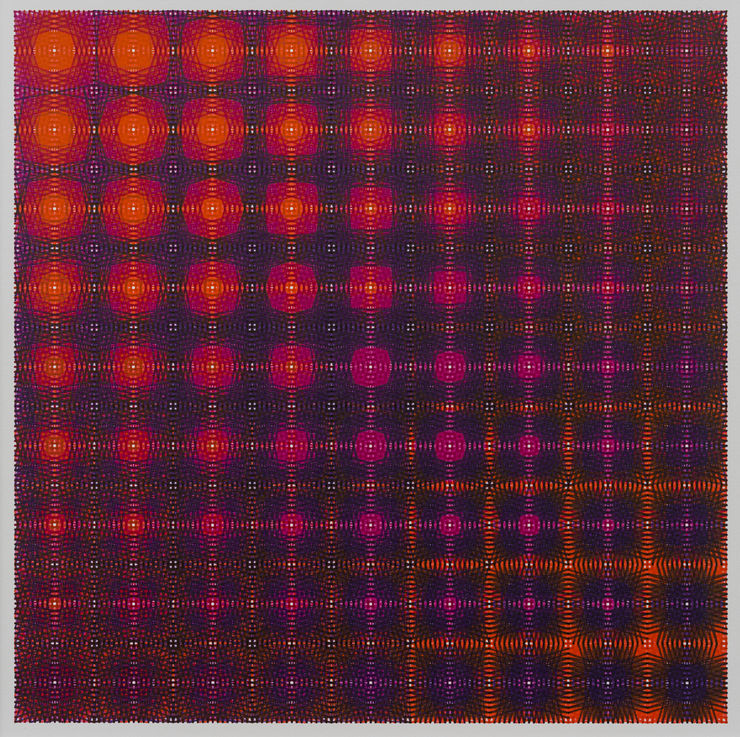

Nima Nabavi, Series 9, Artwork 3 (Orange, Pink, Purple), 2025, Archival Ink on Paper, 9 x 9 in., 23 x 23 cm, 15 x 15 x 1⅛ in. (framed), 38 x 38 x 3 cm (framed)

-

Nima Nabavi, Series 9, Artwork 4 (Pink, Purple, Navy), 2025, Archival Ink on Paper, 9 x 9 in., 23 x 23 cm, 15 x 15 x 1⅛ in. (framed), 38 x 38 x 3 cm (framed)

-

Nima Nabavi, Series 9, Artwork 5 (Purple, Navy, Royal), 2025, Archival Ink on Paper, 9 x 9 in., 23 x 23 cm, 15 x 15 x 1⅛ in. (framed), 38 x 38 x 3 cm (framed)

-

Nima Nabavi, Series 9, Artwork 6 (Navy, Royal, Turquoise), 2025, Archival Ink on Paper, 9 x 9 in., 23 x 23 cm, 15 x 15 x 1⅛ in. (framed), 38 x 38 x 3 cm (framed)

-

Nima Nabavi, Series 9, Artwork 7 (Royal, Turquoise, Green), 2025, Archival Ink on Paper, 9 x 9 in., 23 x 23 cm, 15 x 15 x 1⅛ in. (framed), 38 x 38 x 3 cm (framed)

-

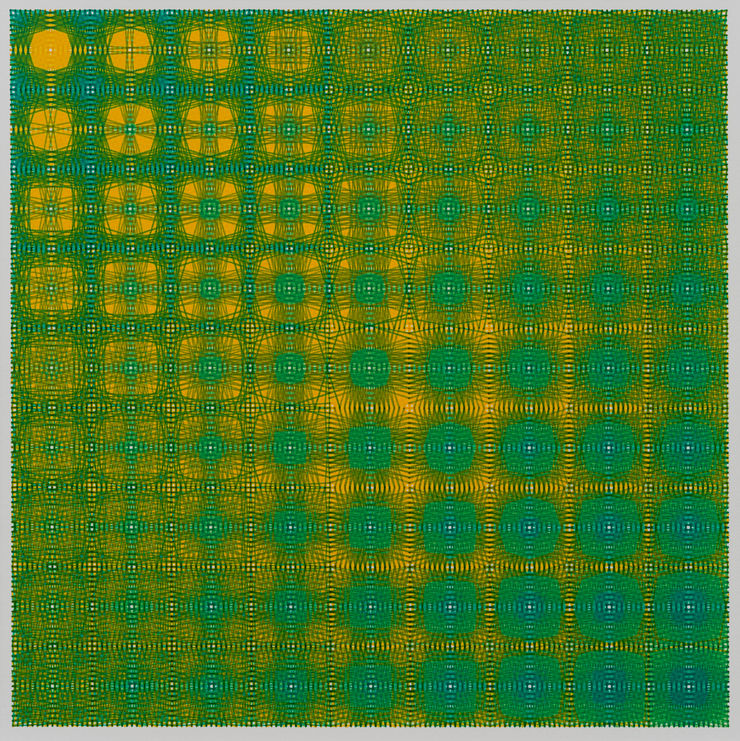

Nima Nabavi, Series 9, Artwork 8 (Turquoise, Green, Yellow), 2025, Archival Ink on Paper, 9 x 9 in., 23 x 23 cm_15 x 15 x 1⅛ in. (framed)_38 x 38 x 3 cm (framed)

-

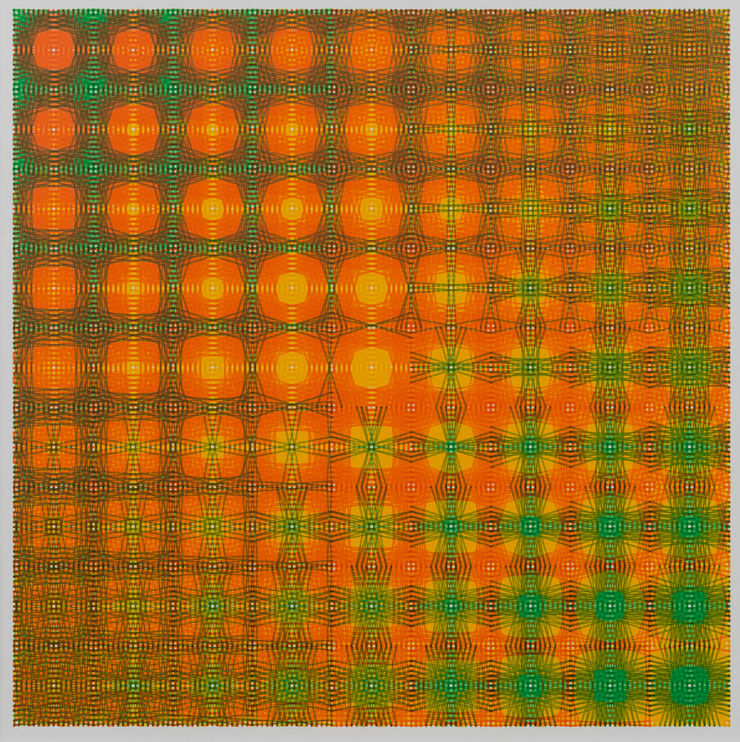

Nima Nabavi, Series 9, Artwork 9 (Green, Yellow, Orange), 2025, Archival Ink on Paper, 9 x 9 in., 23 x 23 cm_15 x 15 x 1⅛ in. (framed), 38 x 38 x 3 cm (framed)

-

Nima Nabavi: Sunrise at the Vortex

Past viewing_room